6316 El Cajon Blvd.

San Diego

CA

92115

Phone: 619-583-8850

Fax: 619-583-6043

Email: info@amisraelmortuary.com

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Bom-Wrapper

Memorial Candle Tribute From

Am Israel Mortuary

"We are honored to provide this Book of Memories to the family."

View full message >>>

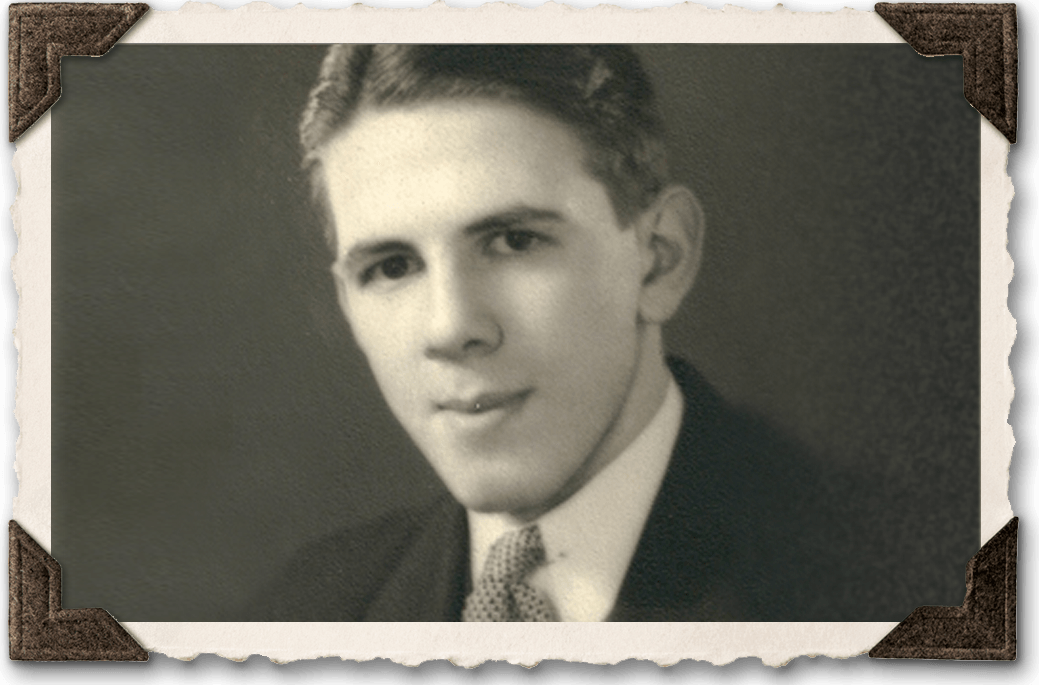

In Memory of

William Barnett

"Bill"

Kolender

"Bill"

Kolender

1935 - 2015

Menu

Life Story for William Barnett "Bill" Kolender

The man who changed the face of local law enforcement in San Diego County and then went on to become one of the most powerful public leaders in the county died Tuesday morning.

Former police chief and sheriff William Kolender was 80. He died after a long battle with Alzheimer's disease.

“He made the world a better place. His heart was always golden and his intentions were pure. I told him that today before he died,” said daughter Randie Kolender-Hock, who was at his bedside at Scripps Mercy Hospital when he passed. “‘Dad, everything you did was good and right.’”

He wore a badge for nearly half a century and, at one time, he was the oldest sheriff in California and one of the oldest in the country.

To his peers, he was the Godfather.

"Bill is a law enforcement legend," said San Diego police Chief Shelley Zimmerman. "His vision of community policing improved the way we police today. Bill’s 50 plus years of service to our San Diego and law enforcement community are evidence of his selfless commitment to helping others."

EDITORIAL In memoriam: Bill Kolender

Kolender’s career in law enforcement began in 1956 when he became a San Diego police officer. He worked for the department until 1988 — the last 13 years as chief. At age 40, he was the youngest big-city police chief when he was appointed in 1975 and he was the department’s first Jewish chief.

He served as assistant to the publisher of the Union-Tribune Publishing Co. in the late 1980s and was appointed director of the California Youth Authority in 1991.

Kolender was first elected sheriff in 1994 after being heavily recruited by the Deputy Sheriffs’ Association and other community leaders.

Dan Mitrovich, former San Diegan and owner of a consulting firm, said it was his idea in 1994 to have Kolender run for sheriff against incumbent Jim Roache.

"Bill was a great friend," said Mitrovich. "He was heading the California Youth Authority for Gov. Pete Wilson. He flew down here (from Sacramento) and we had a three-hour meeting."

He said Kolender agreed to talk over the election prospect with his wife, and they soon agreed to the challenge. "He was elected with 62 percent of the vote," said Mitrovich, a commander in the San Diego County Honorary Deputy Sheriff's Association and a Crime Stoppers board member.

Kolender was re-elected three times with no serious opposition.

Former governor and Sen. Pete Wilson, who was San Diego mayor when Kolender became police chief, said he had recognized Kolender's leadership skills as a police sergeant and wanted him to run for state Assembly. Kolender turned him down.

"He said, 'I think my role is here, in law enforcement,'" Wilson recalled. "He thought he could make a contribution and had ideas on how he could be effective."

Toward the end of his role as sheriff, Kolender began slipping mentally, his friends said. He cut back his hours and started using a driver in 2007, but refused to step down, even after rumors surfaced that he might be suffering from Alzheimer’s or dementia. He confronted the rumors for a front-page story that ran in The San Diego Union-Tribune in October 2007.

He had planned to retire when his term expired in 2011, but he stepped down two years early after acknowledging his diagnosis of Alzheimer's, said his longtime friend Tom Giaquinto. "He did the right thing by retiring when he did," said Giaquinto, a retired San Diego police lieutenant and state parole board commissioner "He brought an awful lot of compassion to all his positions. He was a really good guy."

Sheriff Bill Gore said Kolender was an early champion of jail rehabilitation programs, including re-entry initiatives and educational courses.

"He would always say that we had a moral obligation to (inmates,) besides just keeping them in a clean and safe place, to get

them skills so they can reintegrate into our communities and be productive members of society - not just recycle back through the jail system," Gore said.

Kolender was also recognized for his ability to forge partnerships - with leaders throughout San Diego County's communities and among other law enforcement groups.

Gore, who met Kolender when he was a teen, said he will be remembered most for his personal touch. Whenever a deputy was injured, Kolender went to the deputy’s bedside. If a deputy died in the line of duty, Kolender personally delivered the news to family. Gore said Kolender's ability to connect with and care for others was the underlying key to his success.

"He really cared. You can't fake that," Gore said. "... He spoke to others with attention and respect. He was a great listener. After talking with Bill, you felt he was your new best friend."

Kolender was born May 23, 1935, in Chicago and raised in San Diego. His father worked as a jeweler. His parents didn’t want a cop as a son, but they never imagined it would lead to such a charmed life.

Kolender’s father told him he should choose a more respectable profession, but Kolender thought the work was interesting and he needed the money. His parents couldn’t afford his college tuition.

A part of him always identified with the working class.

“We lived in Hanukkah Heights,” Kolender said in 2007 while referring to the Del Cerro neighborhood where he and his second wife, Lois, lived before moving to Granite Hills. “Back then, they wouldn’t let Jews or people of color live in La Jolla.”

He met Frank Sinatra and Ronald Reagan and he occasionally dined with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and then-wife Maria Shriver.

He enjoyed talking about the moments that shaped him. He was affable and quick with a joke, even when time started catching up with him.

Kolender’s political clout transcended expectations.

Former San Diego police chief and former mayor Jerry Sanders, now CEO of the San Diego Regional Chamber of Commerce, said Kolender was a consummate politician.

“He was probably the best politician in San Diego outside of Pete Wilson,” and knew everybody in the community, Sanders said. “He just was excellent with working with the mayor, with the City Council, with the school district -- with everybody.”

Kolender considered running for mayor in a 1983 special election and again in 1986. After bowing out the second time, he said: “I’m a cop, not a politician.”

He enjoyed a lot of firsts with the San Diego Police Department.

He was promoted to sergeant at 26, the youngest officer to hold the rank at that time. In 1965, he was promoted to lieutenant. Three years later, at 33, he became the youngest captain in department history. In 1971, he was promoted to inspector, and he was named public information officer a year later. In 1973, he became the city’s youngest-ever assistant chief. Two years later, at 39, he became the youngest deputy police chief.

By the time he became chief, his daughter was in high school. It was hard to find other kids to relate to her at times, she remembered, with her father being on the news every evening.

“Whatever my friends did, they hid from me,” Kolender-Hock, of Del Mar, laughed.

Despite the pressures of the job, her father always kept his sense of humor, she said.

“He was really good at scaring the boyfriends that would come over. ... I’ll always miss the way he could tell a joke, unlike no other.”

She remembered when she was a little girl, 11 or 12, and her father and his best friend decided to go off-roading up Cowles Mountain in a Volkswagen Beetle.

"I was crying, I was so scared, and they were just laughing," she recalled.

He was chief during the Brenda Spencer school shooting in 1979 and during the San Ysidro McDonald’s massacre in 1984.

Perhaps his greatest achievement as a police officer was his role in establishing and cementing community-oriented policing. He was the first officer in charge of San Diego’s community relations division, which was created in 1967 to connect beat cops with taxpayers, especially minority and low-income residents. The department still uses community relations officers - now called community resource officers - across the city.

"He was a pioneer in changing how law enforcement interacted with the community and providing his deputies and officers the tools they needed to be professional organizations," said San Diego County District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis.

Like most big-city chiefs in the 1970s and 1980s, Kolender dealt with racial strife.

He established a civilian police review panel in response to complaints of racism within the department, but was criticized for demanding final say over who was appointed to the panel.

During the Sagon Penn trials in the mid-1980s, Kolender angered the black community for defending his officers. Penn killed one police officer and wounded another, but was acquitted of the most serious charges after saying he was beaten by officers and taunted with racial epithets.

At the conclusion of the second trial, Superior Court Judge J. Morgan Lester publicly criticized the San Diego Police Department, which prompted a state attorney general’s investigation. The department was cleared of any wrongdoing.

In 1986, Kolender received a written reprimand from the city manager as a result of an investigation that found Kolender fixed traffic tickets for friends and used a police officer to run personal errands. Kolender admitted fixing several tickets and publicly apologized. “I am wrong and I am sorry,” he said at the time.

Kolender resigned as police chief about a year before a county grand jury issued a scathing report that alleged widespread police misconduct under his command. The report included accusations of corruption and tampering with evidence and suggested officers may have removed names from the Rolodex of Karen Wilkening — the “Rolodex Madam” — who ran a local call girl service.

In June 1991, a new grand jury reversed direction and said there was insufficient evidence to support the allegations. It found no evidence linking Kolender with Wilkening.

When he first ran for sheriff, Kolender received 62 percent of the vote to defeat incumbent Jim Roache in 1994. Four years later, he ran unopposed. In 2002, Kolender received 75 percent of the vote to 25 percent for sheriff’s Sgt. Bruce Ruff. In 2006, Kolender and Ruff squared off again and Kolender cruised to another victory with 70 percent of the vote.

He is credited with modernizing the sheriff department. There was controversy, but very little compared to his time as police chief.

He received the San Diego County Taxpayers Association’s “Golden Fleece Award” because of overtime expenses of $19 million in 1999 — when his overtime budget was $13 million. The department exceeded its overtime budget every year under Kolender. In 1996 and 1997, overtime almost doubled what was budgeted.

He ushered in a new sheriff communications system, new substations in Poway, San Marcos and Fallbrook, and two firefighting helicopters. He also opened a new downtown jail and a regional crime lab.

In October 2007, he said: “I love what I do. I’m still motivated. It’s a pleasure to come to work.”

San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer said Kolender's "influence still resonates decades later and he will be dearly missed.”

Kolender is survived by wife Lois, daughter Randie Kolender-Hock, sons Michael and Dennis Kolender, stepdaughter Jodi Karas, and grandchildren Nathan, Danielle, Taylor, Kendall and Brooklyn.

A public memorial service is being planned and information about it will be released as it becomes available.

This story was written in advance in 2008 by former U-T staff writer Tony Manolatos, now a communications consultant; and U-T researcher Michelle Gilchrist and was updated Tuesday by staff writers Karen Kucher, Pauline Repard, Lyndsay Winkley and Kristina Davis.

Former police chief and sheriff William Kolender was 80. He died after a long battle with Alzheimer's disease.

“He made the world a better place. His heart was always golden and his intentions were pure. I told him that today before he died,” said daughter Randie Kolender-Hock, who was at his bedside at Scripps Mercy Hospital when he passed. “‘Dad, everything you did was good and right.’”

He wore a badge for nearly half a century and, at one time, he was the oldest sheriff in California and one of the oldest in the country.

To his peers, he was the Godfather.

"Bill is a law enforcement legend," said San Diego police Chief Shelley Zimmerman. "His vision of community policing improved the way we police today. Bill’s 50 plus years of service to our San Diego and law enforcement community are evidence of his selfless commitment to helping others."

EDITORIAL In memoriam: Bill Kolender

Kolender’s career in law enforcement began in 1956 when he became a San Diego police officer. He worked for the department until 1988 — the last 13 years as chief. At age 40, he was the youngest big-city police chief when he was appointed in 1975 and he was the department’s first Jewish chief.

He served as assistant to the publisher of the Union-Tribune Publishing Co. in the late 1980s and was appointed director of the California Youth Authority in 1991.

Kolender was first elected sheriff in 1994 after being heavily recruited by the Deputy Sheriffs’ Association and other community leaders.

Dan Mitrovich, former San Diegan and owner of a consulting firm, said it was his idea in 1994 to have Kolender run for sheriff against incumbent Jim Roache.

"Bill was a great friend," said Mitrovich. "He was heading the California Youth Authority for Gov. Pete Wilson. He flew down here (from Sacramento) and we had a three-hour meeting."

He said Kolender agreed to talk over the election prospect with his wife, and they soon agreed to the challenge. "He was elected with 62 percent of the vote," said Mitrovich, a commander in the San Diego County Honorary Deputy Sheriff's Association and a Crime Stoppers board member.

Kolender was re-elected three times with no serious opposition.

Former governor and Sen. Pete Wilson, who was San Diego mayor when Kolender became police chief, said he had recognized Kolender's leadership skills as a police sergeant and wanted him to run for state Assembly. Kolender turned him down.

"He said, 'I think my role is here, in law enforcement,'" Wilson recalled. "He thought he could make a contribution and had ideas on how he could be effective."

Toward the end of his role as sheriff, Kolender began slipping mentally, his friends said. He cut back his hours and started using a driver in 2007, but refused to step down, even after rumors surfaced that he might be suffering from Alzheimer’s or dementia. He confronted the rumors for a front-page story that ran in The San Diego Union-Tribune in October 2007.

He had planned to retire when his term expired in 2011, but he stepped down two years early after acknowledging his diagnosis of Alzheimer's, said his longtime friend Tom Giaquinto. "He did the right thing by retiring when he did," said Giaquinto, a retired San Diego police lieutenant and state parole board commissioner "He brought an awful lot of compassion to all his positions. He was a really good guy."

Sheriff Bill Gore said Kolender was an early champion of jail rehabilitation programs, including re-entry initiatives and educational courses.

"He would always say that we had a moral obligation to (inmates,) besides just keeping them in a clean and safe place, to get

them skills so they can reintegrate into our communities and be productive members of society - not just recycle back through the jail system," Gore said.

Kolender was also recognized for his ability to forge partnerships - with leaders throughout San Diego County's communities and among other law enforcement groups.

Gore, who met Kolender when he was a teen, said he will be remembered most for his personal touch. Whenever a deputy was injured, Kolender went to the deputy’s bedside. If a deputy died in the line of duty, Kolender personally delivered the news to family. Gore said Kolender's ability to connect with and care for others was the underlying key to his success.

"He really cared. You can't fake that," Gore said. "... He spoke to others with attention and respect. He was a great listener. After talking with Bill, you felt he was your new best friend."

Kolender was born May 23, 1935, in Chicago and raised in San Diego. His father worked as a jeweler. His parents didn’t want a cop as a son, but they never imagined it would lead to such a charmed life.

Kolender’s father told him he should choose a more respectable profession, but Kolender thought the work was interesting and he needed the money. His parents couldn’t afford his college tuition.

A part of him always identified with the working class.

“We lived in Hanukkah Heights,” Kolender said in 2007 while referring to the Del Cerro neighborhood where he and his second wife, Lois, lived before moving to Granite Hills. “Back then, they wouldn’t let Jews or people of color live in La Jolla.”

He met Frank Sinatra and Ronald Reagan and he occasionally dined with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and then-wife Maria Shriver.

He enjoyed talking about the moments that shaped him. He was affable and quick with a joke, even when time started catching up with him.

Kolender’s political clout transcended expectations.

Former San Diego police chief and former mayor Jerry Sanders, now CEO of the San Diego Regional Chamber of Commerce, said Kolender was a consummate politician.

“He was probably the best politician in San Diego outside of Pete Wilson,” and knew everybody in the community, Sanders said. “He just was excellent with working with the mayor, with the City Council, with the school district -- with everybody.”

Kolender considered running for mayor in a 1983 special election and again in 1986. After bowing out the second time, he said: “I’m a cop, not a politician.”

He enjoyed a lot of firsts with the San Diego Police Department.

He was promoted to sergeant at 26, the youngest officer to hold the rank at that time. In 1965, he was promoted to lieutenant. Three years later, at 33, he became the youngest captain in department history. In 1971, he was promoted to inspector, and he was named public information officer a year later. In 1973, he became the city’s youngest-ever assistant chief. Two years later, at 39, he became the youngest deputy police chief.

By the time he became chief, his daughter was in high school. It was hard to find other kids to relate to her at times, she remembered, with her father being on the news every evening.

“Whatever my friends did, they hid from me,” Kolender-Hock, of Del Mar, laughed.

Despite the pressures of the job, her father always kept his sense of humor, she said.

“He was really good at scaring the boyfriends that would come over. ... I’ll always miss the way he could tell a joke, unlike no other.”

She remembered when she was a little girl, 11 or 12, and her father and his best friend decided to go off-roading up Cowles Mountain in a Volkswagen Beetle.

"I was crying, I was so scared, and they were just laughing," she recalled.

He was chief during the Brenda Spencer school shooting in 1979 and during the San Ysidro McDonald’s massacre in 1984.

Perhaps his greatest achievement as a police officer was his role in establishing and cementing community-oriented policing. He was the first officer in charge of San Diego’s community relations division, which was created in 1967 to connect beat cops with taxpayers, especially minority and low-income residents. The department still uses community relations officers - now called community resource officers - across the city.

"He was a pioneer in changing how law enforcement interacted with the community and providing his deputies and officers the tools they needed to be professional organizations," said San Diego County District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis.

Like most big-city chiefs in the 1970s and 1980s, Kolender dealt with racial strife.

He established a civilian police review panel in response to complaints of racism within the department, but was criticized for demanding final say over who was appointed to the panel.

During the Sagon Penn trials in the mid-1980s, Kolender angered the black community for defending his officers. Penn killed one police officer and wounded another, but was acquitted of the most serious charges after saying he was beaten by officers and taunted with racial epithets.

At the conclusion of the second trial, Superior Court Judge J. Morgan Lester publicly criticized the San Diego Police Department, which prompted a state attorney general’s investigation. The department was cleared of any wrongdoing.

In 1986, Kolender received a written reprimand from the city manager as a result of an investigation that found Kolender fixed traffic tickets for friends and used a police officer to run personal errands. Kolender admitted fixing several tickets and publicly apologized. “I am wrong and I am sorry,” he said at the time.

Kolender resigned as police chief about a year before a county grand jury issued a scathing report that alleged widespread police misconduct under his command. The report included accusations of corruption and tampering with evidence and suggested officers may have removed names from the Rolodex of Karen Wilkening — the “Rolodex Madam” — who ran a local call girl service.

In June 1991, a new grand jury reversed direction and said there was insufficient evidence to support the allegations. It found no evidence linking Kolender with Wilkening.

When he first ran for sheriff, Kolender received 62 percent of the vote to defeat incumbent Jim Roache in 1994. Four years later, he ran unopposed. In 2002, Kolender received 75 percent of the vote to 25 percent for sheriff’s Sgt. Bruce Ruff. In 2006, Kolender and Ruff squared off again and Kolender cruised to another victory with 70 percent of the vote.

He is credited with modernizing the sheriff department. There was controversy, but very little compared to his time as police chief.

He received the San Diego County Taxpayers Association’s “Golden Fleece Award” because of overtime expenses of $19 million in 1999 — when his overtime budget was $13 million. The department exceeded its overtime budget every year under Kolender. In 1996 and 1997, overtime almost doubled what was budgeted.

He ushered in a new sheriff communications system, new substations in Poway, San Marcos and Fallbrook, and two firefighting helicopters. He also opened a new downtown jail and a regional crime lab.

In October 2007, he said: “I love what I do. I’m still motivated. It’s a pleasure to come to work.”

San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer said Kolender's "influence still resonates decades later and he will be dearly missed.”

Kolender is survived by wife Lois, daughter Randie Kolender-Hock, sons Michael and Dennis Kolender, stepdaughter Jodi Karas, and grandchildren Nathan, Danielle, Taylor, Kendall and Brooklyn.

A public memorial service is being planned and information about it will be released as it becomes available.

This story was written in advance in 2008 by former U-T staff writer Tony Manolatos, now a communications consultant; and U-T researcher Michelle Gilchrist and was updated Tuesday by staff writers Karen Kucher, Pauline Repard, Lyndsay Winkley and Kristina Davis.

Recently Shared Condolences

-

Oh my dearest Lois.....know... (read more)

Recently Lit Candles

-

We are honored to prov ...(read more)

Recently Shared Stories

-

Bill was my chief a... (read more)

Am Israel Mortuary

6316 El Cajon Blvd.

San Diego

CA

92115

Phone: 619-583-8850

Fax: 619-583-6043

Email: info@amisraelmortuary.com